John Oswald, a Scottish Jacobin

Taking a break from my multi-part series for a standalone article on a truly wild life

John Oswald had been born in Edinburgh in 1760, a son of either a blacksmith or an innkeeper. It is said that it was his father who gave him his love of writing and literature. That is surprising, because neither profession is usually associated with such passions. On the other hand, late 18th century had seen a great growth in popular novels, literary journals, and accessible circulating libraries; these latter allowed even people of modest means to access books in exchange for a small regular fee. Edinburgh was a major city - perhaps, the elder Mr. Oswald was a devoted subscriber of one?

Whether or not it was the case, he clearly had ambitions for his son, and arranged an apprenticeship with a goldsmith for him. It was the most prestigious trade a young man working with his hands could enter. However, the young John dreamed of adventures, not labouring in a workshop, however prospectively well-paid. At only sixteen, he rebelled against his father’s wishes, and joined the army. His superiors soon saw his bravery as well as his education - in 1780, when he was sent to India with the 42nd Regiment of Foot, he did so in the rank of a lieutenant. A gifted autodidact, he had taught himself Latin and Ancient Greek. Later, he will also master fluent Arabic, Portuguese… and, what would turn out to be incredibly important to his future, French.

In India, John fought in the Second Anglo-Mysore War up to its ending in 1783. Then, likely to many people’s surprise, he suddenly resigned from the army.

His reasons for that were so astonishing that, had a fictional character in a historical novel exhibited them, critics would have raised their eyebrows. He had spent a lot of time in close contact with the locals, and it led him to realize that the British colonial efforts were much more barbarous than anything the native Indians could muster. Moreover, he developed such an appreciation towards the local culture that he even converted to vegetarianism.

It must be said, however, that personal grief must have played a role in it. He was very young when he had married a woman named Louisa - about whom we know nothing, except the fact that she gave him two sons and was devoted enough to accompany John to India (which, in the days before Victorian era, was not usual, much less expected, from the officers’ wives). Neither do we know the cause of her death - although, if we were to choose the most likely cause, the climate and the unusual (for Europeans) diseases of the subcontinent were probably the reasons for Louisa’s demise.

Year 1784 saw John, now a widower with two children, in London. The polyglot warrior was now a polyglot political journalist.

He had seen, in the colonial service, many instances of what his contemporary (and fellow Scotsman) poet Burns had called “man’s inhumanity to man”; and, for that matter, man’s inhumanity to other creatures. It was time to persuade the world.

John soon found work in a newspaper called British Mercury. It supported Charles Fox - the most radical (by pre-French Revolution standards) of major Whig politicians, who, among other things, defended the American colonies’ struggle for independence against his own country.

Like many British radicals of the decade, John was interested in the ideas of French thinkers who wanted to reform (no one then spoke of overthrowing) the absolute monarchy. He even shared the same circles with Brissot - possibly even spent time with him - when the future leader of the Girondins visited London in 1784.

In the spring of 1790, John took a momentous decision: he left his safe (well, relatively safe - the increasingly conservative Pitt the Younger was now the Prime Minister, after all…) career in London and moved to Paris. There, he took part in the founding of a newspaper called The Universal Patriot - fittingly, it was written in English, but printed in France, and aimed at reporting on the political developments in both countries. In September 1791, he became one of the poets who presented the recently-elected National Assembly with an ode celebrating freedom.

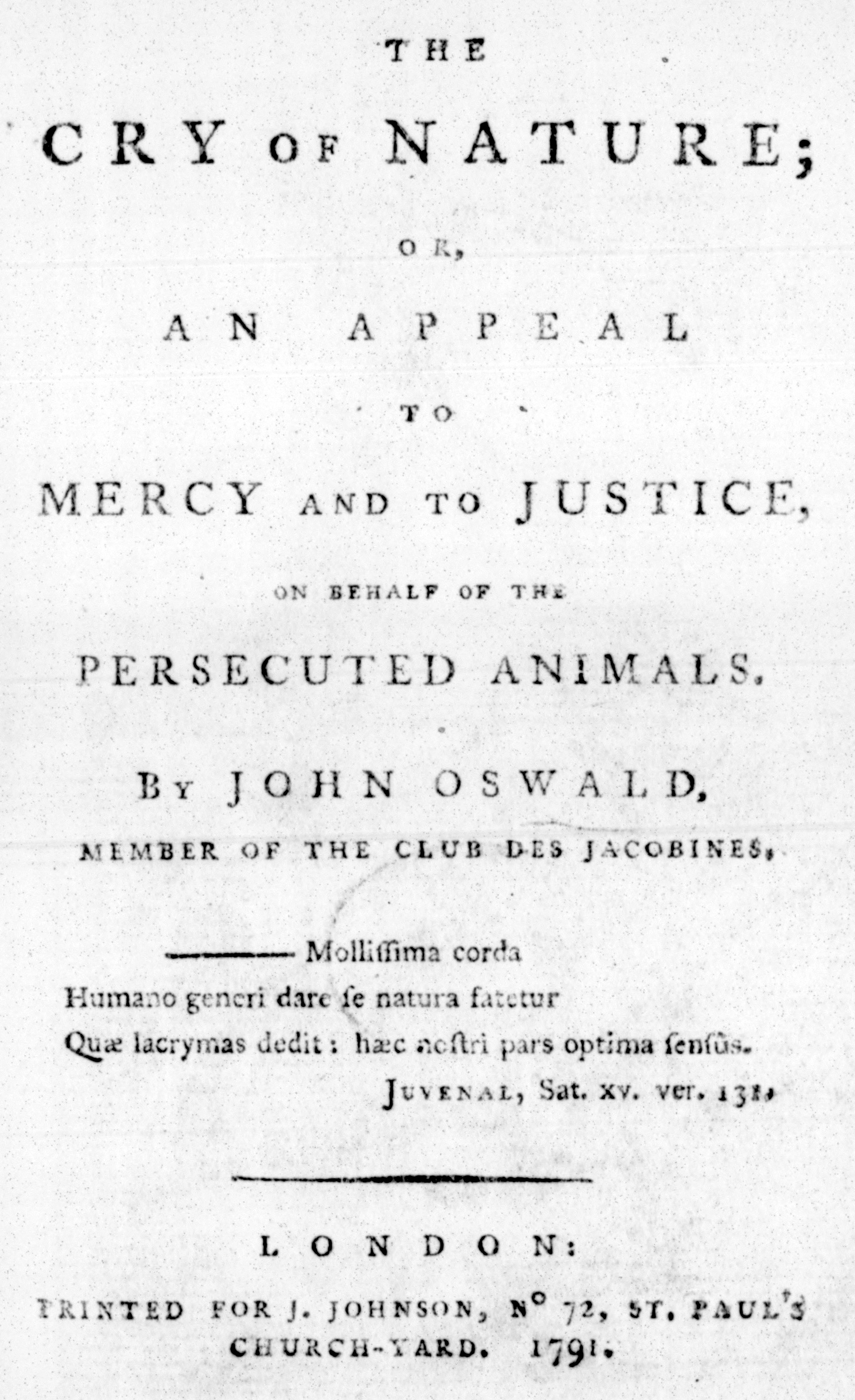

In the same year, John Oswald wrote a startling tract called Cry of Nature - it not only argued that compassion and kindness towards animals are good natural impulses that had only been numbed by the cruel society people lived in, but even that vegetarianism (that he himself espoused) should be a part of that kindness.

It was around the same time that he began his journey into serious political controversy. During a visit home, he spoke at the Society for Free Debate - a London-based political club - that the Parliament was a “monstrous” thing, corrupt and only serving the interests of the most privileged of the privileged men. The country should, he argued, follow the French example, and elect something like the National Assembly, supported by local assemblies in the provinces, without any of the property-based restrictions on voting that prohibited most men from having a voice in the elections. For the time (he made his speech in the end of 1790), it was a very radical notion. Honestly, even among the literal Jacobins across the Channel, the ideas of a direct democracy would only become mainstream no earlier than 1792.

Oswald was not the only foreigner in Paris in those years: Étienne Claviers, one of the creators of the assignats - the new paper money for the new country - was from Geneva; plenty of Belgians who failed in their own efforts to oust the Prince-Bishop of Liege and establish a new republic there came to France; the Prussian Johann von Cloots defended the project of the ‘universal republic’ in his speeches there. And, well, let’s not forget the ladies: Helen Williams, the radical English poetess, even took part in organizing the first anniversary of the fall of the Bastille.

After some time, John Oswald started addressing the Jacobins with petitions to help the British radicals who were being persecuted by Pitt. He even proposed that the revolutionaries supported societies beyond the Channel that were sympathetic to their cause. However, his suggestions were defeated; the leaders of this most famous of political clubs argued that intervening in the affairs of a country France was not at war with would be a dangerous folly.

In August, the situation changed somewhat; while things like armed support or financial help were still denied, the French agreed to send an official brotherly address to the radical clubs in Britain. Apart from the greetings and words of support, the address included a complete account of the recent proceedings of the National Assembly, as well as copies of the papers of Louis XVI that confirmed his secret dealings with the Austrians (dealings that, had any ordinary man been implicated in them, would have been called high treason).

Two weeks after this decision, John Oswald received an offer of French citizenship, and accepted it gladly.

Thanks to John Oswald’s prior military experience and evident dedication to the ideals of the new republic, he was appointed a commander in the new French Revolutionary army. It is said that he had organized a dance for his battalion to celebrate the execution of Louis XVI (sources are silent as to whether it was a proper ceilidh).

An official club for the English, Scottish, and Irish allies of the revolution had been officially created on the 7th of January, 1793. It agreed to meet at the place unofficially named ‘Hotel de White’ (no relation to the supremely snobbish White’s gentlemen’s club in London; the hotel was simply owned by a wine merchant called Christopher White). All kinds of people were members - from lawyers and chemists to fiery playwrights and such singular personalities as Edward Fitzgerald (dubbed ‘Citizen Lord’), a great Irish nationalist who wanted not just to liberate his country, but to turn it into a democratic republic. Oswald became the club’s secretary.

In May 1793, Oswald took command of the Parisian battalion of pikemen, later designated the 14th battalion of Paris, and joined the fighting in war against the royalist uprising in the Vendee. He had distinguished himself in several engagements.

He died at Thouars on 14 September 1793. He was only thirty-three years old. His brave adolescent sons, who followed him into the army, died with him, killed by grapeshot.

Oswald did not live a long life, and the republic to which he had pledged himself outlived him only by a little while. His name, however, remained awe-inspiring to the people of later decades, who struggled against the injustices of the Victorian world, while modern defenders of animal rights credit him as one of the founders of their philosophy.