Drinking Like a Regency Buck

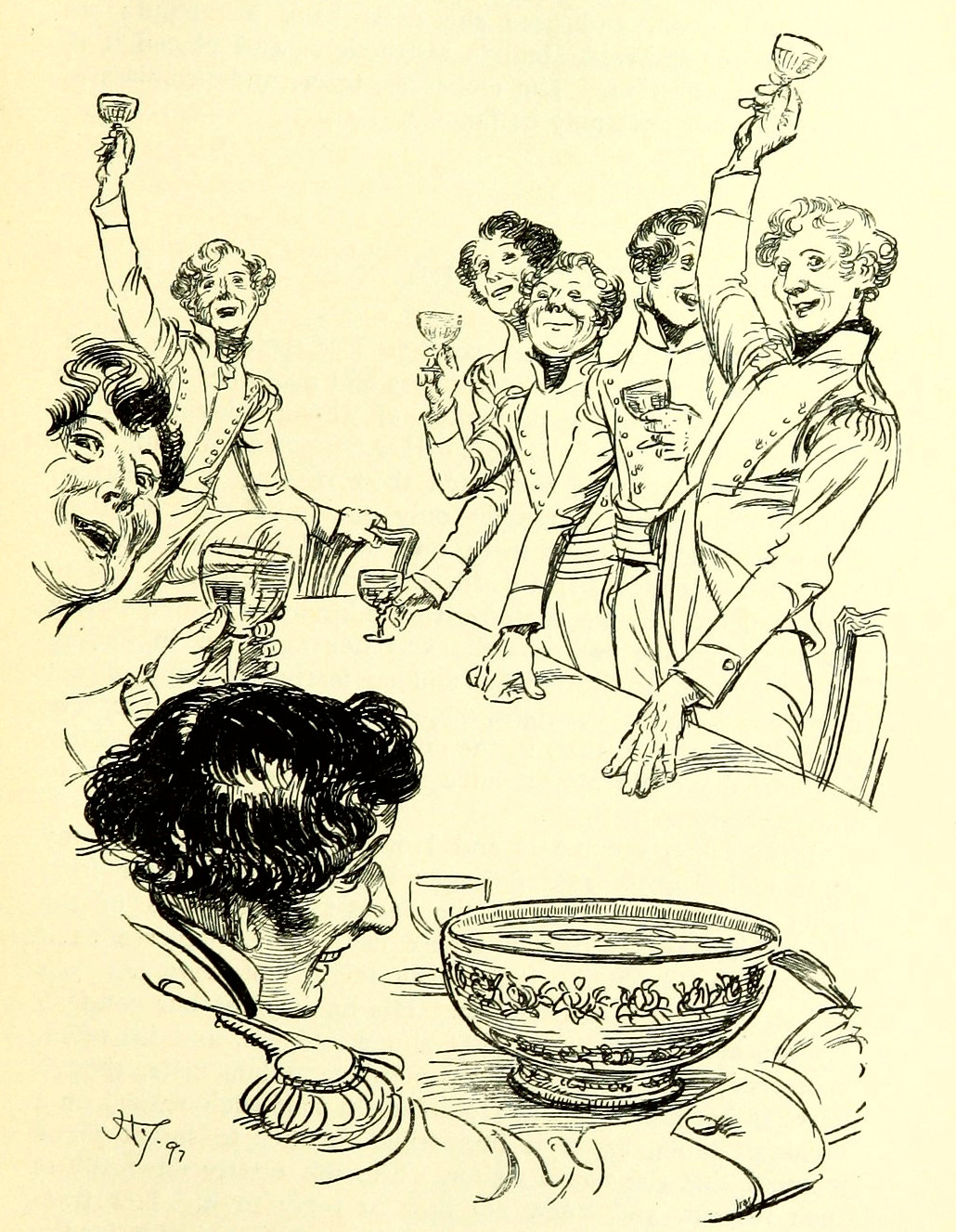

What if you were praised for drinking lots of alcohol? In Regency England, you could be! Well… if you were a wealthy man.

Nowadays, we think that immoderate drinking is a sign of weakness. However, back in the 1800s, it was often considered to be something between a neutral trait and, in some circles, a proof of hardiness.

A popular expression on the subject was ‘three-bottle man’. It described a man who could consume 3 bottles of port throughout one day and remain on his feet. Again, it was not necessarily a derogatory expression. It was, indeed, not unusual to have several dinner guests like that at one table.

Strong port was the most popular drink of choice for Regency men. It used to be different – earlier in the 18th century they preferred light wines and claret. However, after the Seven Years War, the blame for the country’s poor performance in the conflict was laid at the feet of the men’s ‘effeminate’ and ‘Frenchified’ drinking habits. No, it was not blamed on alcohol consumption per se; the problem, according to the writers of the day, was that the consumption in question was not masculine enough. So, the gentlemen set out to prove how manly they were, and that’s where the port came in.

Due to port’s popularity, plenty of people ended up trying to play foul with its quality for the sake of profit. Quite often, port was adulterated by raisin wines, or cheap Spanish wine that had a name of ‘bullock’s blood’. Even worse, some just used berry-dye for the same purposes.

However, even good port had to be ‘fined’, or clarified, before you could drink it. There was a great range of things used for that purpose. Some were mundane enough, like egg, salt, or skimmed milk. Some were weirder, like oyster shells, alabaster, dry sand, or my favorite option because of how elegant it sounds – powdered marble.

Henceforth, claret, once a favorite of both sexes, was usually only served to women, and that in special claret cups. (Though, I do have to say, some Regency ladies were far from the Victorian ideals of propriety and sobriety, too – a number of them drank fortified wine such as madeira.)

Say, you didn’t like port, and actually preferred Scottish whiskey. Then, well… you were in a bind, because during the war with France – and most of the Regency period was consumed by the war with France – taxes and regulations made trading in good Highland whiskey very difficult. Naturally, that did not mean that the trade stopped; the drinking most certainly had no intention of stopping. The solution was obvious: smuggling.

Whiskey-smuggling for the moneyed consumers became quite endemic. Indeed, it became such a lucrative enterprise that smugglers even started to travel in large paramilitary bands, sometimes disguised as a squad of soldiers or even preceded by pipers (!). The methods were really quite ingenious – if you are interested, I can do a whole post on the tales of Regency whiskey smuggling one day.

I need to explain here that buying from smugglers, whatever exactly you were buying, was not actually some rare and shadowy offense committed in dark alleyways. Take the famous (to the fans of the era) parson James Woodforde, the renowned diarist who was, well, a parson. He led a quiet life, and was utterly foreign to any concept of either skulduggery or swashbuckling. However, at one point, on one late evening, he noted in his journal – and rather nonchalantly at that – that he had just had a rendezvous with a smuggler to replenish his supplies.

Granted, the good parson, being both a sober and sober-minded person, was merely buying his tea – always a safer choice!